Torshällas first Ironworks

Nyby works all know, but how many people remember the predecessor Holmen mills in Torshälla? There was pounding of the iron ore into malleable rods already in the 1600s - with Thor's hammer at the ready. East of the river, below Holmberg, was a water-powered hammer, as citizen Jacob Persson built in the 1630s. The business had been down at times, but the 1670s saw a major expansion under new owners.

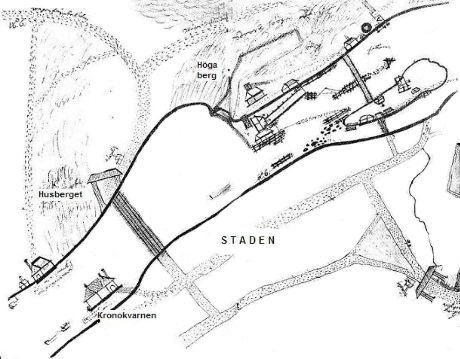

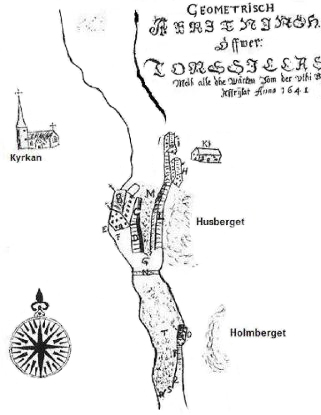

On a land survey map in 1685, as shown above, you can see to the left Husberget and top right, next to Eskilstunavägen, the "High mountain", ie Holmberg. The image has been oriented so that the water in the river flows from the upper right corner diagonally down to the left. At Husberget low customs gate, drawing plant, Crown Flour Mill and large bridge over the river. The ironworks was at Holmberg right of the image. Several buildings, paths, bridges and water channels are visible there clearly. Some lay on the islet in the river, and from there to the bridge that links both sides of the river. Even on a geometric map from 1641 you can see below Holmberg a flume and a smaller bar hammer, which belonged to the citizen Jacob Persson. The hammer is marked with the letter O on the map, and the water channel appears at the letters PR and S. of the compass on the old map seen from the north-south compass rose on the left. The latter map is then rotated slightly more than a quarter turn counterclockwise in relation to this.

Most of the iron ore came from Nora in Örebro County. The iron was transported first to Skärmarbrink just north of Örebro and then via Hjalmaren, Hyndevad and Eskilstunaån Torshälla, where it was stored for forwarding by sea to Stockholm1. Rod Iron-making required a lot of charcoal. Forest must be harvested in large quantities. Additionally hydropower was needed to drive the big hammers. Such natural resources were not everywhere in sufficient quantities. The great iron bolt manufacturer Lohe continually complained of timber shortage in this neighborhood, which was one of the reasons that he moved to the new opportunities that the crown offered him in the woods of Arable and Länna. At this time the crown encouraged new businesses, including giving a six-year tax exemption. For anyone with this jump-starting the successful start up of hammering, then waiting for the little dissuasive one per cent tax on production. Besides Holmen mills in Torshälla there were several mills in the river where the drop height was big enough. Lohe drove a tilthammer in Tunafors and Hyndevad , and at present Faktoriholmarna was a smaller hammer at Rademachersmedjorna that lay along the river. There were conducted contemporary high-tech; so-called WHITESMITHERY and cold sheet metal works . It was a question of making tools, delicate locks, scissors and the like, not just spikes and needles. A small hammer was also driven by Kaspar Grau at Näshulta mill . It was so small it did not even exist! It required permission at this time to get the manufacture of bar iron, and Kaspar did not have this, but apparently it went well2. Möhlmans hammer and Leijel’s rose Maria Leijel’s grandfather Andreas Dress was a wealthy and enterprising man who gained business skills by working as a bookkeeper for the great Louis de Geer. He succeeded in capturing the lease on the Crown foundries, mines and hammers in Nora and Linde mining areas in 1631, and revenue collection in Fellingsbro, Nasby and Ervalla parishes landed on his head. Something he was not too happy about. You would think that it was just the rich Andreas Dress which once had bought Jacob Persson's hammer in Torshälla. But relations between Nora and Torshälla were numerous. Sven Björnsson Möhlman’s father was an alderman in Torshälla and could also afford to buy the hammer of Jacob. Sven was in all cases rich through his marriage with Maria Leijel, ironmaster at Hammarby Mill , which she inherited from her grandfather. It was common at this time that the husband acted as if the wife's property was also his own. Therefore, one cannot be sure that" Möhlmans hammer," as it is called in land books, ever belonged to Mohlman himself. The Leijel dynasty was quite large and still has descendants through the female line in Sweden. Three Leijel brothers had immigrated to Stockholm in 1638 and established themselves as merchants. They came from the port town of Arbroath about two miles northeast of Dundee on the Scottish east coast. Another branch of the family became merchants in London which facilitated exports of the Swedish relatives. Also Maria Leijel’s three uncles were ironmongers and mill owners . Her uncle David drove Älvkarleby and Harnäs works in Uppland, and her ten years younger cousin Adam Leijel married Hedvig Lucia Lohe and became involved in Biby Manor and Hellefors metal works in Little Mellösa parish, which Hedwig Lucia had inherited from her father. Maria Leijel had a brother also named Adam Leijel. He became director of Hellefors Silver Mill in Örebro County. He was knighted for his contributions to the promotion of mining, took over Rockhammar and Hammarby from his father and bought with his sister, Maria Leijel, Norrby works in Fellingsbro parish. When Adam died unmarried without heirs in 1729 his three sisters inherited and Maria's part went to her only son Jacob Mohlman. He became the new works patron at Hammarby.

Both Mohlman, as did his widow and her relatives, lived as did many other mill owners and merchants in their own palaces on the wharf in Stockholm. It was their headquarters, you could say. They were very focused on information and had good links with the Crown Representatives of Mines and the College. In an age without a newspaper, telephone, car, rail or internet, it was important that the owner personally was in a place where decisions were made. The local operations on Leijels various mills were led by the works bookkeeper who could be more or less independent in relation to the owner. However, there is no reason to believe that Maria Leijel took a less active part in service activities than other mill owners just because she was a woman. Understanding of the operations In Näshultaån Maria Leijel built a new hammer and a large pond. She got right to expand the business since she lent large sums of money to the owner of the land, the Baroness Catharina Elisabeth Kurck of Bergshammar. Since the noble lady's husband, Colonel Knut Kurck, had been captured during Charles XII's Russian war she ended up in monetary trouble. The couple also owned the nearby Hedensö. There Maria Leijel’s employees felled lots of wood which was mostly taken to the mill in Torshälla. She also bought more forests and land in Raby - Rekarne parish, and long quarreled with her tenant Olof Andersson in Bånkesta to buy the old abbey estate from the crown. Olof offered stubborn resistance. Although he did not have the money to buy the farm, he strove so long under the right of first refusal because he lived there that Maria lost patience and gave him a cash sum that he might move. It cannot have been easy for him to leave the farm where he and his family had lived for several years. Sometime later he figures among the bankruptcies in the District Court's protocol. Maria became involved further in a protracted succession dispute on the neighbouring farm of Ökna. By lending money to one party she avoided that the farm's 120 hectares of forest land ended up in the hands of Lohe’s service managers. She was also in a dispute with a poor farmer in Ljusberg for having during a cold winter chopped firewood on her estate in nearby West Kolsta. But the peasant was right! Court investigation showed that the farm Ljusberg had been created as a registered homestead of Ökna and West Kolsta. Thus it was clear! Farmers in such salvaged homestead (bolbyar4) had the right to cut wood so long as it was done for subsistence. And that was exactly what Nils in Ljusberg had done. Apparently Maria Leijel was missing knowledge of this ancient Swedish peasant practice, conceived in the often scarce and meager conditions that existed here in the countryside in the past. Our female ironmaster tax also bought several farms in Torshälla parish, Upper and Lower Källsta , Årby and Mälby and she also tried to buy Nyby and Väsby Holm. She had no lack of money, but the chief service man in Livgedinget advised her not to. It was the well-known Nils Adel Stierna who supplanted Leijel by himself buying both farms. This caused problems for Holmen mills which were dependent on supplies of charcoal. Mrs Leijel became Mrs Snack Works widow Maria Leijel remarried in 1706 with a member of the Board of Trade. His name was Peter Snack and was born in Nyköping. His brothers were knighted by the name Sneckenberg. Peter himself was appointed governor of Gotland in 1713, but died on the journey there . Maria Leijel was called after this marriage mostly "Fru Snack" in the documents , but that was hardly the case of any coffee party aunt! She was one of the two female mill owners who appeared in Eskilstuna region in the 1700s. The second was Anna Blume, a confectioner’s daughter from Stockholm who married Johan Lohe on Biby, but that's another story. If you can, among other things, read in Lars Widdings book about LohesTreasure in the Old Town of Stockholm. Iron mill further fate depicted in the words and picture of Leif Persson in Torshälla ABC. Notes: Source: Torshällas first Ironworks, by Thomas Gustafsson Link |

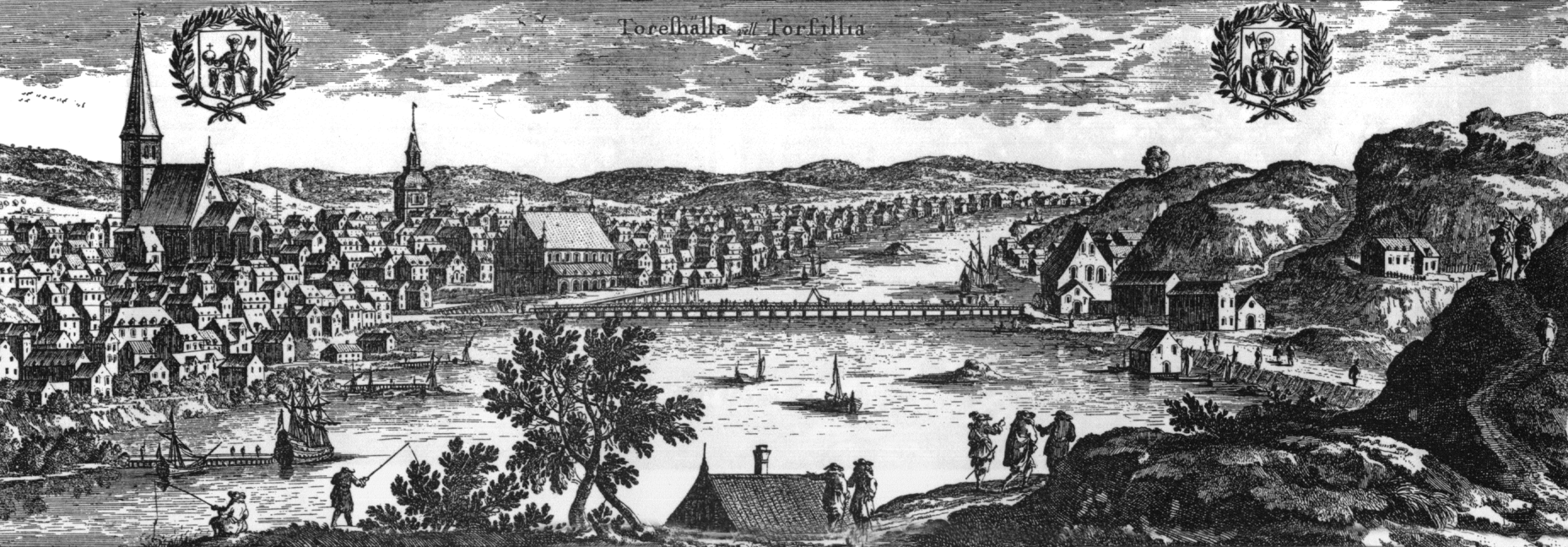

Torshälla (engraved ca. 1695) from Erik Dahlberg's Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna, Vol 2

Torshälla (engraved ca. 1695) from Erik Dahlberg's Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna, Vol 2