Music process in 1800Text: Erik & Marta Ronne Published in Ergo 1-1999, Uppsala Student newspaper The waves that the French Revolution created also led at the periphery of Europe to a ripple on the surface of the otherwise tranquil Uppsala. The 1790s were characterized throughout by a political awareness in Uppsala, which was only again reached in the late 1960s. Suddenly people questioned the establishment, arguing for their rights and stood up in opposition to it. The forum for this revolutionary awareness became “The Junta” - an association of Republican students who directly challenged the monarchy and the Gustavian autocracy. For a few years the Junta became one of the most important opinion leaders in Swedish politics and incredibly important for Swedish culture. The Junta and the republican tendencies in Uppsala were only finally humbled at the so-called music trial in 1800.

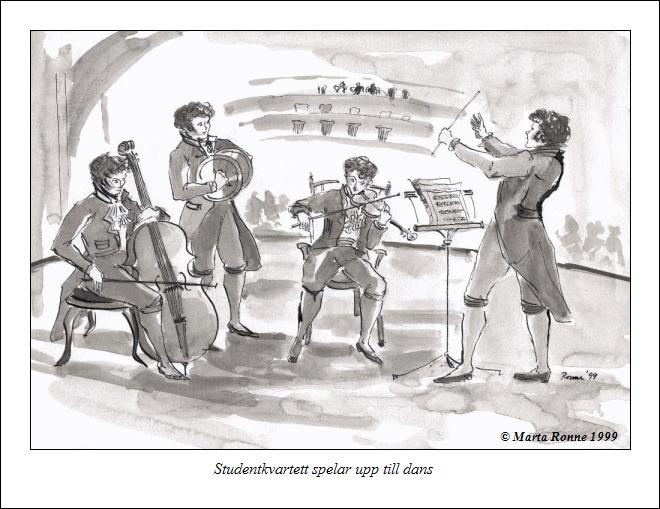

The origin of this strange and somewhat student advantageous lawsuit was in the coronation of King Gustav IV Adolf and his Queen Frederica of Baden in Norrkoping on the 3rd of April 1800. It became the most unsuccessful coronation in Swedish history: it was sleeting and in full storm when the procession would take place. Even before the procession walked away Gustav's horse reared and the magnificent coronation mantle was soiled with mud and slush. A little later, Gustav’s horse started stalling and refusing to take a single step, so that Gustav was eventually forced to change horse. The rod of the Swedish banner blew off in the storm and not a single person of Norrköping ventured out into the storm to cheer. At the crowning the crown chafed a bleeding wound on the newly anointed king’s head. The dinner has been described as a culinary disaster and the night after the coronation, the pregnant Queen Fredrika became ill and had a miscarriage. Even in Uppsala the failed coronation would become a laughing-stock. The University governing board had decided that the crowning act ought to be commemorated locally, and arranged a special academic coronation feast in the Gustavianum. Orations to extol the new king would be by Theology. Prof. Almquist and the students' representative Doc. Kolmodin. To further embellish the feast it was determined that fitting music would be played by the Academic Orchestra under the direction of Director of Music Leyel - a person, by some means musical, but foolish, and bordering on imbecilic lieutenant. This appeared a brilliant opportunity for the Junta to make fun of the king and the monarchy. Many of the Junta’s members were musical and several of them, including the Junta's key figure Doc. Silfverstolpe played as a so-called amateur in the Academic Orchestra. For Silfverstolpe it was a cinch to convince the very meager talented Leyel that the pompous regal Bataille de Fleurus of Hessler would fit well at such a time. The piece was unfamiliar to Leyel, but after an audition, he could only agree with Silfverstolpe. What Leyel did not know or understand was that Hessler in its composition, as later Lennon-McCartney in Love, love, love, borrowed the musical theme from the Marseillaise. Silfverstolpe and the Junta's cunning calculation was that the hideous revolutionary anthem would be played to celebrate the coronation of one of Europe's most rabid detractors of the French Revolution. The rumour about the planned coup spread however in student circles and, just before the feast would take place, the rumour reached even up to the Rector Magnificus. He took Leyel by the ear and forbade on the spot the performance of Bataille de Fleurus. The frightened Leyel, who did not understand what the commotion was, assembled quickly, and tried to retreat by suggesting that the Academic Orchestra might be able to perform a symphony by Haydn instead. When the musicians a moment later appeared they noticed to their surprise that the notes of the music stands were not of Bataille de Fleurus, but a symphony of Haydn. Leyel did not wish to admit to the orchestra that he had been told by the director himself, but pleaded instead that he had unfortunately forgotten the notes to Bataille de Fleurus at home, and that the time was too short to run home and fetch the notes. The musicians were naturally outraged that their prank could not be launched, and the most affected of all was Silfverstolpe. He explained that it was contrary to his artistic beliefs to change repertoire immediately before the feast since the Academic Orchestra have not had the opportunity to practice enough the symphony by Haydn. Upset, he left the Gustanavium just before the orchestra would appear before the public. After him the members of the Junta, and also other amateurs soon packed up their instruments and left the stage. The musicians went straight to Östmarks basement, where they took a hefty breakfast and proposed a series of bowls and hurrahs for the Republic, the power of the people and freedom of expression, but hardly any for the newly crowned king. What happened at the feast of the Gustavianum? Well, Leyel “kept his face in the cruel game” and performed the symphony almost entirely without musicians. Only three musicians were left. Their instruments and voices were quite disparate, and in addition, they were untrained, which only led to a terrible cacophony, that probably would not have made Haydn particularly happy. Those of the students present, however, liked Leyel’s interpretation of Haydn. They applauded happily, and some even began to dance. Although there was no Marseillaise as the coronation music one rejoiced in Östmarks basement for they had at least succeeded in creating ridicule over the ceremony. Not for long, however, was there a reason to rejoice. Shortly after the spectacle Silfverstolpe and six other of the Junta’s members of the Academic Orchestra were sued in the Consistorium Minus. The trial that followed, the so-called music trial, dragged on and attracted a lot of attention throughout the country. Above all Silfverstolpe’s many ironic and sarcasticly written submissions were referenced around the country. Towards the end of the trial the highly controversial Hans Järta stood up as defense attorney for the Junta. This was perhaps to the Junta's disadvantage - Järta had himself angered the royalist circles in connection with Gustav IV's coronation in Norrköping when he renounced his knighthood and changed his name from Hierta to Järta. The Junta received opinion and the students on its side, but the verdict was no less severe. Silfverstolpe was sentenced to lose his lectureship and received lifetime banishment from the academy and Uppsala. Several other Junta members also lost their academic titles and relegated different number of years, and were sentenced to 8 days imprisonment in Proban. The unfortunate less-knowledgeable Leyel eventually lost his ministry. Already at that time the judgment was considered a clear miscarriage of justice and appealed by the junta in two steps: First, to the university chancellor and then to his royal majesty himself, but the one who got his sentence mitigated was Leyel who slipped away with a warning. The music trial in 1800 was definitely Uppsala’s fatal blow to the Junta. A decade of political commitment and student greenish opposition to the Gustavian absolutism was ended. For both the Swedish culture as also life at Uppsala University were expecting some years of stagnation. But the romance was imminent This article is part of a series of 123 articles by Erik Ronne & Marta Ronne published in Uppsala Student newspaper Ergo during 1994-2005. The article is published on leijel.se courtesy of Marta Ronne English translation: Mats Eriksson and Peter Leyel

|